Awards and Decisions

ICSID tribunal dismisses final claim for compensation in relation to Hungary’s 2008 termination of power purchase agreement

Electrabel S.A. v. Republic of Hungary, ICSID Case No. ARB/07/1

Matthew Levine [*]

A Belgian energy company—Electrabel S.A. (Electrabel)—has failed in its final claim under the Energy Charter Treaty (ECT). An International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) tribunal has found no breach of the ECT’s fair and equitable (FET) treatment standard by Hungary.

In 2012 the ICSID tribunal had issued a decision dismissing three minor claims and postponing the fourth, major claim for a second phase of proceedings. The 2015 award (Award) orders Electrabel to cover the fees of the arbitration.

Background

In 1995 Dunamenti (operator of Hungary’s largest power plant, then wholly-owned by Hungary) and MVM (Hungary’s sole wholesale electricity buyer, 99.9 percent owned by Hungary) entered into a Power Purchase Agreement (PPA). Subsequent to the PPA, a group of foreign investors, including Electrabel, invested substantial funds in Dunamenti as shareholders.

Hungary acceded to the European Union in 2004. Between December 2005 and June 2008, the European Commission conducted a formal investigation into unlawful state aid provided by Hungary under, among other instruments, the PPA. In June 2008, the European Commission issued a final decision in relation to the investigation (EC Final Decision). In December 2008 Hungary terminated the PPA.

In June 2007 Electrabel commenced the present arbitration in anticipation of the PPA’s termination. In March 2009, on the initiative and agreement of the parties, the tribunal ordered a first phase of proceedings addressing only issues of jurisdiction and liability. This procedural order also contemplated a second phase of proceedings to address quantum issues. Of note, the European Commission intervened in the first phase of proceedings to argue that Electrabel’s claims did not fall within the jurisdiction of an international arbitral tribunal, as they were understood to be exclusively covered by European law.

At the end of November 2012, the tribunal issued its Decision on Jurisdiction, Applicable Law and Liability (2012 Decision). The tribunal found its own jurisdiction in relation to all of Electrabel’s claims under the ECT. With regards to liability, the tribunal dismissed three minor claims brought by Electrabel and dismissed all grounds for liability under the claimant’s fourth and final claim—the PPA Termination Claim—with one exception, namely, that Hungary had failed to provide FET in calculating costs incurred by Electrabel for the purpose of granting compensation.

In early 2015, arbitration proceedings initiated by E.D.F. International in relation to a similar investment in Hungary resulted in an arbitration award. Electrabel and Hungary made short written submissions regarding the E.D.F. award.

The 2012 Decision: PPA Termination Claim

In the first stage of proceedings, the tribunal considered the PPA Termination Claim in relation to both ECT Article 13(1) (expropriation provision) and ECT Article 10(1) (FET provision). The tribunal found that there had been neither direct nor indirect expropriation of Electrabel’s investment.

In relation to Hungary’s alleged failure to provide FET, the tribunal briskly dismissed Electrabel’s claim in relation to events prior to the EC Final Decision. It found, rather, that Electrabel’s claim turned primarily on results of the European Commission investigation. “In the Tribunal’s view, that [EC] Final Decision required Hungary under EU law to terminate Dunamenti’s PPA, as explained below. The Tribunal also draws a distinction between the [EC] Final Decision in regard to recoverable State aid and Hungary’s own scheme for calculating Stranded Costs (with Net Stranded Costs)” (para. 6.70).

In the Decision, the tribunal therefore concluded that Hungary could only be liable in the present arbitration under ECT Article 10(1) for its application of EU law in determining Electrabel’s stranded costs for the purpose of compensation. While the methodology prescribed under EU law resulted in a range of values, Electrabel was disappointed to have been compensated the minimum amount under that methodology.

The 2015 Award: Fair & Equitable Treatment (FET) in calculating Net Stranded Costs

In the Award the tribunal considered Hungary’s implementation of the European Commission’s methodology for calculating Net Stranded Costs to determine whether it violated ECT Article 10(1).

The tribunal explained that both Stranded Costs and Net Stranded Costs are terms of art in EU law. In considering whether Hungary’s calculation of Electrabel’s Net Stranded Costs ran afoul of Hungary’s obligations under ECT Article 10(1), the tribunal noted that it had already rejected, in the 2012 Decision, any allegation of discriminatory measures, and that Electrabel made no allegations regarding either lack of transparency or due process.

Therefore, as put concisely by the tribunal, the principal issues arose in regard only to arbitrariness and frustrated legitimate expectations. In general it was Electrabel that bore the burden of proving its case under the ECT’s FET standard.

Absence of arbitrariness

In terms of Electrabel’s claim of arbitrariness, the tribunal applied an objective test in the circumstances prevailing at the relevant time. The tribunal found itself in agreement with previous tribunals, such as Saluka, AES, and Micula, in that a measure will not be arbitrary if it is reasonably related to a rational policy. And, following the AES tribunal especially, this required two elements: the existence of a rational policy and the state acting reasonably in relation to that policy.

The tribunal considered the following arguments by Electrabel, among others: first, Hungary’s decision as to the level of compensation was driven by a desire to minimize the associated burden on the national budget; and second, Hungary had decided against compensation even before the extent of losses resulting from the PPA’s termination could have been known.

The tribunal noted that Hungary’s scheme was not devised by the Hungarian Parliament for Dunamenti alone, but for an entire industrial sector. It also noted that these had been turbulent economic times, with Hungary’s economy facing severe financial and fiscal constraints. Relevant negotiations were difficult and protracted. The tribunal observed that it would be all too easy, many years later with hindsight, to second-guess a state’s decision and its effect on a single entity such as Dunamenti, when the state was required at the time to consider much wider interests in awkward circumstances, balancing different and competing factors. Further, even as regards only Dunamenti, Hungary sought to balance several appropriate considerations.

Ultimately, the tribunal found that Electrabel had not proven that “Hungary’s conduct was arbitrary or that there was no legitimate purpose for Hungary’s conduct or that Hungary’s conduct bore no reasonable relationship to that purpose or was, in another word, disproportionate” (para. 168).

Lack of legitimate expectations

As regards legitimate expectations under the ECT’s FET standard, the tribunal found no evidence that Hungary represented to Electrabel, at the times of its investments in Dunamenti, that it would ever act differently from the way that it eventually did act towards Dunamenti or Electrabel. And, in the absence of such a representation, the tribunal found that Electrabel’s case on legitimate expectations could not succeed.

The tribunal concluded that Electrabel’s case appeared to rest upon purported representations concerning pricing arrangements. However, the statements in question did not amount to a representation (or assurance) that Dunamenti would be entitled to a reasonable profit or that Electrabel would be entitled to a reasonable return on its investment. Furthermore, in the tribunal’s view, any such entitlement would have been inconsistent with the terms of the PPA: although in this case the place for such an entitlement would have been in the PPA from 1995 onwards, it was evident that, under the PPA, Dunamenti bore the risk of a change in the applicable law.

Furthermore, the tribunal noted that “the application of the ECT’s FET standard allows for a balancing exercise by the host State in appropriate circumstances. The host State is not required to elevate unconditionally the interests of the foreign investor above all other considerations in every circumstance. As was decided by the tribunals in Saluka v Czech Republic and Arif v Moldova, an FET standard may legitimately involve a balancing or weighing exercise by the host State.” (para. 165).

Tribunal notes E.D.F. award

The tribunal noted that it may be perceived as being at variance with the E.D.F. tribunal. Although the tribunal had considered the parties’ submissions on the E.D.F. award, it found it inappropriate to further dissect the E.D.F. award in search of evidence and arguments.

The tribunal could not be “influenced therefore by the result of a different arbitration, where an investor’s claim appears to have been formulated differently and decided on different arguments and evidence” (para. 225). The tribunal went on to note that the E.D.F. award had also declined to compensate the investor for the maximum amount of Net Stranded Costs.

Costs

The tribunal found that the parties should be responsible for their own legal costs and expenses. Electrabel, however, was required to cover the fees and expenses of the arbitrators as well as ICSID’s administration fees.

Notes: The tribunal is composed of V. V. Veeder, (President, British national), Gabrielle Kaufmann-Kohler (claimant’s appointee, Swiss national), and Brigitte Stern (respondent’s appointee, French national). The Award was dispatched to the parties on November 25, 2015 is available at http://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/case-documents/italaw4495.pdf

Tribunal dismisses all claims by U.S. mining investor against Oman

Adel A. Hamadi Al Tamimi v. Sultanate of Oman, ICSID Case No. ARB/11/33

Stefanie Schacherer [*]

A tribunal at the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) dismissed all claims against Oman, in an award dated November 3, 2015. The claimant was

Adel A. Hamadi Al Tamimi, a U.S. investor with controlling majority shareholdings in two mining companies operating in the Persian Gulf region. In 2006, he had concluded lease agreements with an Omani state-owned mining company for the quarrying of limestone in the municipality of Mahda in Oman.

The investor’s claims for expropriation, breach of minimum standard of treatment and breach of national treatment arose out of Oman’s alleged harassment and interference in the operation of his mining companies, which culminated in the termination of the relevant lease agreements by the state-owned company as well as the confiscation of the mining facilities by the Royal Oman Police. The dispute fell under the Oman–United States Free Trade Agreement (FTA), which entered into force in January 2009. The claimant sought compensation of around US$560 million.

Background

Al Tamimi made his investment in 2006 through two lease agreements for the quarrying of limestone signed between each of his companies, Emrock and SFOH, and the Omani state-owned enterprise Oman Mining Company LLC (OMCO). Only Emrock was duly registered in Oman. Subsequently, the Omani Ministries of Finance and Environment issued to Al Tamimi the initial permits. Both ministries reminded him to respect the limits of the quarrying area and to limit his activity to the exploitation of limestone products. Al Tamimi thus started to operate in the Jebel Wasa mountain range in September 2007.

Quickly however the relationship between Al Tamimi, OMCO and the ministries deteriorated. The Ministry of Environment issued a number of complaints, warnings and fines against Emrock, SFOH and OMCO, notably because of the Al Tamimi’s alleged takings of material from the Jebel Wasa area, operation of machinery without the necessary permits, failure to obtain permits for housing, and uprooting of trees. The claimant did not take into account any of these complaints.

The situation culminated in OMCO’s decision to terminate the agreement with Emrock, and to declare the agreement with SFOH to be null because of the initial failure to register the company in Oman. A July 2008 letter notified Al Tamimi of these decisions, and a second letter followed in February 2009 confirming the termination of the lease. As the claimant did still not stop to operate, the ministries and OMCO issued further warnings, and ultimately the Royal Oman Police arrested Al Tamimi at the request of the Ministry of Environment for the alleged unauthorized operation.

Jurisdiction ratione temporis: only Emrock–OMCO agreement was covered by the FTA

The tribunal engaged in a long discussion as to its jurisdiction ratione temporis given that the Oman–United States FTA entered into force only on January 1, 2009, whereas the two lease agreements had already been concluded in 2006. The FTA does not apply to investments made before its entry into force. The question therefore was whether the lease agreements still were valid after January 1, 2009.

In relation to the Emrock–OMCO agreement, the tribunal analyzed the two letters of termination of the lease. It did not consider the first termination notice by OMCO in July 2008 to be effective. Indeed, the tribunal found that even after July 2008 OMCO continued to communicate with Emrock and the Omani government about the lease. Furthermore, the tribunal considered that the subsequent termination notice of February 2009 superseded the earlier notice. As such, the tribunal considered that the Emrock–OMCO lease was still in force until February 2009 and thus fell under the Oman–United States FTA.

With respect to the SFOH–OMCO agreement, however, the tribunal declined its jurisdiction. It held that OMCO’s declaration was effective as of July 2008, and OMCO was entitled to treat the lease agreement as null and void because of SFOH’s failure to register and obtain business licenses in Oman.

Expropriation claim dismissed

Al Tamimi listed a series of actions taken by Oman that led to the complete loss of his investment, thus alleging a type of creeping indirect expropriation. The central element of the expropriation claim was the termination of the two lease agreements, which initially gave the investor the right to operate in Jebel Wasa. However, this right finally ceased to exist in February 2009, as the tribunal already decided in its jurisdictional analysis. Al Tamimi argued that the termination of the lease agreements was unlawful.

The tribunal did not engage in a discussion about the unlawfulness of the termination, since this question would fall under private contract law rather than public international law. In other words, the claimant’s investment was lost not as the result of sovereign expropriation, but as the result of a contractual dispute with a party that was acting in a private commercial capacity. Furthermore, the tribunal held that any action after the termination of the lease agreement could not have interfered with Al Tamimi’s rights, because any property rights ceased to exist with the termination of the lease. Thus, the tribunal dismissed the expropriation claim.

Minimum standard of treatment: content and alleged breach

The Oman–United States FTA specifically refers to customary international law for the content of the minimum standard of treatment. Therefore, the tribunal briefly analyzed previous cases that discussed the content of the standard, mainly in the NAFTA context (such as SD Meyers v. Canada and International Thunderbird v. Mexico). The tribunal reiterated that the minimum standard of treatment under customary international law imposes a relatively high threshold for breach. In the tribunal’s view, in order to establish a breach of the minimum standard of treatment under the Oman–United States FTA, “the Claimant must show that Oman has acted with a gross or flagrant disregard for the basic principles of fairness, consistency, even-handedness, due process, or natural justice expected by and of all States under customary international law” (para. 390). The tribunal underlined that this would not be the case for every minor misapplication of a state’s laws or regulations. That is particularly so, in a context such as the Oman–United States FTA, “where the impugned conduct concerns the good-faith application or enforcement of a State’s laws or regulations relating to the protection of its environment” (para. 390).

Al Tamimi also argued that Oman violated the requirement of proportionality through the termination of the lease agreements as well as through the measure taken by the police. The tribunal rejected this argument and held that the minimum standard of treatment under customary international law does not include a standalone requirement of proportionality of any state conduct that would in fact entail a general obligation of proportionality.

Given the high threshold for breach of the standard, the tribunal dismissed all of Al Tamimi’s allegations concerning unfair conduct and lack of transparency by the Omani ministries. It underlined that, even if there might have been some inconsistency in the way the ministries handled the permits, this would not amount to “manifest arbitrariness” or a “complete lack of transparency and candor” (para. 384).

Furthermore, the tribunal rejected Al Tamimi’s argument as regards the measures taken in order to force him to cease the operation in Jebel Wasa, notably his arrest. According to the tribunal, the actions taken were in full compliance with national law and a consequence of his unlawful presence at the quarry after the termination of the lease agreement. It therefore dismissed the claim for violation of the minimum standard of treatment.

No breach of national treatment after termination of the lease agreement

Al Tamini’s last claim was for an alleged breach by Oman of the national treatment standard enshrined in the Oman–United States FTA. The tribunal reiterated that any action taken by Oman after the termination of the lease agreement could not constitute a breach of his rights under this treaty, since his investment ceased to exist upon termination of the agreement. The tribunal noted that in any event his claim for breach of national treatment would fail due to the lack of reliable evidence. Al Tamini based his evidence merely on a discussion about other quarries in the area that he had with the operator of a neighboring quarry.

All claims dismissed; Al Tamimi ordered to reimburse 75 per cent of Oman’s costs

In view of the above considerations, the tribunal rejected all Al Tamimi’s claims, and ordered him to bear his own costs and to reimburse 75 per cent of the sum of Oman’s arbitration costs, legal fees and other expenses.

Notes: The tribunal is composed of David A. R. Williams (President appointed by the parties, New Zealand national), Charles N. Brower (claimant’s appointee, U.S. national), and Christopher Thomas (respondent’s appointee, Canadian national). The award of November 3, 2015 is available at http://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/case-documents/italaw4450.pdf.

ICSID tribunal declines jurisdiction in case against Macedonia and orders investor to reimburse 80% of Macedonia’s legal fees and expenses

Guardian Fiduciary Trust Ltd, f/k/a Capital Conservator Savings & Loan Ltd v. Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, ICSID Case No. ARB/12/31

Inaê Siqueira de Oliveira [*]

In an award dated September 22, 2015, a tribunal at the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) declined jurisdiction to hear the case initiated by Guardian Fiduciary Trust Ltd (Guardian) against Macedonia based on the Netherlands–Macedonia bilateral investment treaty (BIT). The tribunal concluded that Guardian failed to present evidence that it qualified as a national of the Netherlands under BIT article 1(b)(iii).

Factual background and claims

Guardian is a trustee company and financial services provider, constituted under the laws of the New Zealand, which has operated in Macedonia since 2007. In August 2009, following investigations into money laundering initiated in the United States, Macedonian authorities arrested one of Guardian’s directors and issued a press release disclosing the name of the company and of the director arrested.

According to Guardian, Macedonia knew or should have known that the money-laundering allegations were false and that Macedonia’s measures—particularly the statements made to the press—forced Guardian to change its name and the location of its operations, resulting in “substantial damages to its business” (para. 4). Guardian asked for compensation for alleged losses of more than US$600 million, later reducing its claim to approximately US$20 million.

At Macedonia’s request, the tribunal agreed to bifurcate the proceedings, suspending the analysis of the merits to rule, as a preliminary question, on one of Macedonia’s objections to jurisdiction—namely, whether Guardian satisfied the nationality requirement under the BIT.

Summary of claims

In its jurisdictional objection, Macedonia argued that Guardian did not qualify as a national of the Netherlands under BIT article 1(b)(iii), as it was indirectly controlled by Capital Conservator Group LLC (CCG), constituted under the laws of the Marshall Islands.

Guardian, in turn, maintained that it qualified as a national of the Netherlands under the BIT, as it was indirectly controlled by Stichting Intetrust, a Dutch foundation. The fact that it was owned by Capital Conservator Trustees Ltd (CCT), which was in turn owned by IN Asset Management, both New Zealand companies, was irrelevant to the case, given that a legal person constituted under the laws of the Netherlands lied at the end of the chain of ownership.

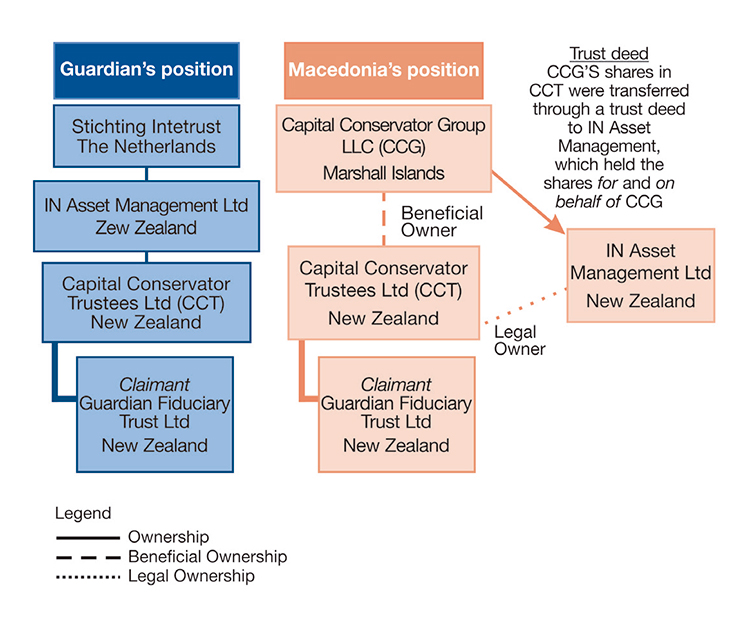

In sum, the parties’ views of Guardian’s corporate structure can be illustrated as follows:

Opposing interpretations of the term “controlled” in BIT article (1)(b)(iii)

In its relevant part, BIT article 1(b)(iii) reads that “[t]he term ‘national’ comprises […] legal persons not constituted under the law of the Contracting State, but controlled, directly or indirectly, by natural persons as defined in (i) or by legal persons as defined in (ii)” (emphasis added). The parties presented opposing interpretations of the meaning of the term “controlled.”

Macedonia asserted that the term “controlled” required not only evidence of ownership, but also evidence of exercise of active control over Guardian’s activities. From Macedonia’s standpoint, the mere legal ownership of shares, for instance, would not suffice to establish control in the absence of evidence of exercise of control.

Guardian, on the other hand, argued that “controlled” refers to the legal capacity of control rather than to the fact of control. Ownership, in Guardian’s view, is sufficient to establish control.

On the interpretation of article (1)(b)(iii), the tribunal initially recognized that “ownership generally implies the legal right or the capacity to exercise control” (para. 131). However, it pointed out that the issue of control was particularly complicated in the present case because of a trust deed between IN Asset Management and CCG, a Marshall Islands company.

Tribunal looks at Guardian’s corporate structure

Macedonia objected to Guardian’s qualification as a national of the Netherlands based mainly on a trust deed of October 1, 2008. According to this trust deed, IN Asset Management, the third element of Guardian’s chain of ownership, held the shares in CCT (which directly owned Guardian) as a trustee for and on behalf of CCG, a Marshall Islands company. In view of this deed, Macedonia asserted that IN Asset Management legally owned CCT as a nominee trustee acting only in a professional capacity, and that CCG retained the beneficial ownership.

Guardian did not deny that CCG was the beneficial owner of CCT. It denied, however, that the deed was relevant to the tribunal’s assessment of jurisdiction. In Guardian’s view, CCG’s role in this corporate structure was passive, and IN Asset Management, as the legal owner of CCT, controlled the shares and held all voting rights. As IN Asset Management was, in turn, controlled by Stichting Intetrust, Guardian asserted that it qualified as a national of the Netherlands.

The tribunal, in its analysis, noted that the terms of the deed made no reference to the direction and control of CCT’s business activities or to the exercise of voting rights. According to the tribunal, this implied that the deed had left open the possibility that control of CCT could have been exercised by IN Asset Management or, indirectly, by Stichting Intetrust. As a result, the tribunal concluded that the issue of control was ultimately a matter of evidence of whether Guardian was effectively controlled by Stichting Intetrust.

Guardian fails to present conclusive evidence that it was controlled by Stichting Intetrust

Guardian presented only one evidence that it was controlled by Stichting Intetrust—a sworn statement of Nicolaas Francken, one of Stichting Intetrust’s owners, saying that the ultimate controlling shareholder of CCT was Stichting Intetrust. In the tribunal’s view, such statement did not provide any further detail on how shareholder control, including voting rights, was in fact exercised.

The absence of evidence led the tribunal to conclude that Guardian failed to qualify as a national of the Netherlands within the meaning of BIT article 1(b)(iii). Consequently, the tribunal dismissed the case for lack of personal jurisdiction.

Reimbursement of Macedonia’s costs

The decision acknowledged that the practice of ICSID tribunals in awarding costs “is not entirely consistent” (para. 149), which it considered as a result of the considerable degree of discretion that the tribunals enjoy under ICSID Convention article 61(2). When using the so-called degree of discretion, the decision referred that the “costs follow the event” approach was appropriate in view of the circumstances of the present case, although without elaborating on what these circumstances were.

The tribunal ordered Guardian to reimburse 80 percent of the Macedonia’s legal fees and expenses. This decision resulted in a reimbursement of US$1,072,708 and £32,800. The tribunal also ordered the parties to share arbitration costs.

Notes: The ICSID tribunal was composed of Veijo Heiskanen (President appointed by the Secretary-General of ICSID, Finnish national), Andreas Bucher (Claimant’s appointee, Swiss national), and Brigitte Stern (Respondent’s appointee, French national). The award is available at http://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/case-documents/italaw4447.pdf.

Quiborax awarded US$50 million against Bolivia, one-third of initial claim

Quiborax S.A. and Non-Metallic Minerals S.A. v. Plurinational State of Bolivia (ICSID Case No. ARB/06/2)

Martin Dietrich Brauch[*]

On September 16, 2015, a tribunal at the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) ordered Bolivia to pay approximately US$50 million in compensation for the expropriation of a mining investment. The claimants were Chilean company Quiborax S.A. (Quiborax) and Bolivian-incorporated Non-Metallic Minerals S.A. (NMM), majority owned and established by Quiborax as its investment vehicle to extract ulexite in Bolivia.

Background and claims

The Gran Salar de Uyuni, a salt flat in the Bolivian region of Potosí, has been a reserve since 1965. Bolivian Law No. 1854 of 1998 (Ley Valda) reduced the size of the reserve, and several mining concessions were requested and granted in the former reserve area. Between 2001 and 2003, Quiborax acquired 11 mining concessions, which were transferred to NMM.

Local communities did not favour the mining concessions in the area. This led Potosí representatives to present bills to reverse Ley Valda and transfer the concessions to the state. Accordingly, Law No. 2564 was promulgated in December 2003, abrogating Ley Valda. The law also authorized the executive to audit the concessions granted while Ley Valda was in force, and to annul the mining rights of concessionaires that were liable to sanctions, reverting the concessions and non-metallic resources to the state.

Based on tax and customs irregularities found in the audits, Bolivia revoked all of NMM’s mining concessions by Decree 27,589 of June 23, 2004 (Revocation Decree). In compliance with the decree, NMM handed over the operation of the concessions to the Potosí administration within 30 days of their revocation. The legality of the Revocation Decree was later questioned, as the mining code provided for the annulment of mining concessions, but not for their revocation. Attempting to remedy the situation, Bolivia abrogated the Revocation Decree itself in December 2005, at the same time annulling the concessions.

One month after the Revocation Decree, Quiborax and NMM requested consultations under the Bolivia–Chile BIT, and ultimately filed arbitration on October 4, 2005; proceedings commenced in December 2007. Among other claims, they argued that the Revocation Decree directly expropriated NMM’s investment (the concessions) and indirectly expropriated Quiborax’s investment (its shares in NMM), and that the expropriation was unlawful. They asked for compensation of US$146,848,827, plus compound interest, and US$4 million for moral damages.

Tribunal finds that illegal conduct during the operation of an investment does not bar an investor from relying on guarantees under a BIT

Bolivia objected that the investments could not benefit from BIT protection as they were neither made nor operated in accordance with Bolivian law. The tribunal reasoned that “ongoing illegality” in the operation of the investment could not affect the availability of BIT protections. As to the allegation of an “original illegality,” the tribunal recalled its jurisdictional decision that the investments were made in accordance with Bolivian law. While Bolivia offered new evidence that the investments were fraudulently acquired, the tribunal found it to be inconclusive.

Bolivia had also argued that the concessions were irregular and void from the outset, and therefore the investors did not have any rights subject to protection. But the tribunal did not support this argument. It found evidence that “the annulment […] was an ex post attempt to improve Bolivia’s defense in this arbitration, not a bona fide exercise of Bolivia’s police powers” (para. 139). Furthermore, looking at Bolivian law, the tribunal held that the alleged irregularities were non-existent or did not serve as grounds for annulment.

Tribunal finds expropriation unlawful despite legitimate public interest at stake

The tribunal was not convinced that the tax and customs irregularities mentioned as grounds for the Revocation Decree really occurred. Even if they did, the tribunal did not find the revocation was justified under Bolivian law. In view of evidence that the claimants were not notified of the audits and did not have access to information about them, the tribunal held that the revocation failed to comply with due process under international law and Bolivian law.

Endorsing the direct expropriation standard enunciated in Burlington v. Ecuador, on which the claimants relied, the tribunal held that the Revocation Decree had resulted in a permanent deprivation of the claimants’ investment, without justification as a legitimate exercise of the Bolivia’s police powers. Therefore, it upheld the claim that the Revocation Decree directly expropriated NMM’s investment in the concessions.

The tribunal also addressed the claimants’ claim that the Revocation Decree indirectly expropriated Quiborax’s shares in NMM. According to the tribunal, since the concessions appeared to be NMM’s only business, without them the shares in the company were “virtually worthless” (para. 239), resulting in an indirect expropriation of Quiborax’s investment in NMM.

Based mostly on media reports about the public perception that the claimants’ mining activities consisted in the looting of national wealth by Chilean investors, the tribunal considered that there was compelling evidence of a discriminatory intent in targeting NMM because of the Chilean nationality of Quiborax. Further, the tribunal had already decided that the expropriation was not carried out in accordance with the law, and it was undisputed that the claimants were not compensated. Accordingly, the tribunal held that the expropriation was unlawful under the BIT.

Even though the tribunal deferred to “Bolivia’s sovereign right to determine what is in the national and public interest” and accepted that “Bolivia may have had a legitimate interest in protecting the Gran Salar de Uyuni Fiscal Reserve” (para. 254), it found that this was irrelevant as the tribunal had already determined on other grounds that the expropriation was unlawful.

Both revocation and subsequent annulment breached FET standard

Without much analysis and leaving open the question of whether the BIT’s fair and equitable treatment (FET) standard corresponded to the minimum standard under international law, the tribunal considered that even under a more demanding standard the revocation of the concessions breached international law, as it was discriminatory and unjustified under domestic law. Again recalling that the annulment appeared to have been a strategy to legalize the revocation when the Revocation Decree was questioned, the tribunal held that the annulment also breached FET.

Tribunal dismisses claims for declaratory judgment and moral damages

The claimants alleged that Bolivia engaged in post-expropriation acts of harassment—mainly by initiating criminal cases against shareholders of the claimants—and that this breached the FET standard and the non-impairment clause under the BIT. However, the tribunal did not find sufficient evidence of such conduct. The tribunal also dismissed the claimants’ allegations that Bolivia, through its procedural conduct in the arbitration, breached several provisions of the ICSID Convention and its duty of good faith. Accordingly, the tribunal dismissed the claimants’ request for a declaratory judgment.

Furthermore, the tribunal understood that the US$4 million in moral damages sought by the claimants were intended to repair non-material damage resulting from the alleged post-expropriation acts of harassment. As the tribunal had already dismissed such alleged breaches, it held that there was no basis for a moral damages claim.

Full reparation valuated under DCF method; calculation based on the date of the award

In accordance with customary international law—as articulated in the Chorzów case and the International Law Commission (ILC) Articles on Responsibility of States for Internationally Wrongful Acts—the tribunal held that the claimants were entitled to full reparation. In the circumstances of the case, it did not see any relevant mitigating factors.

The parties agreed that the reparation should reflect the fair market value of the investment. However, for the valuation, the claimants favoured the discounted cash flow (DCF) method, while Bolivia favoured considering the net amounts invested. The tribunal sided with the claimant, noting that the DCF method is widely accepted, is mentioned in the World Bank Guidelines on the Treatment of Foreign Direct Investment, and has been endorsed by many investment tribunals. It decided to focus on assessing the fair market value of the mining concessions, NMM’s primary asset, and found that the record of operations and prospective profitability of NMM’s mining activity justified applying the DCF method.

The claimants maintained that compensation should be calculated based on the award date, while Bolivia argued that it should be calculated based on the expropriation date. After carefully analyzing the parties’ submissions and the reasoning in Chorzów, a majority of the tribunal decided to quantify the losses on the date of the award, considering that the expropriation was unlawful for various reasons, not only because it lacked compensation. In support of its decision, the majority cited to other investment tribunals, adjudicatory bodies and scholars following the same approach. Brigitte Stern, arbitrator appointed by Bolivia, wrote a partially dissenting opinion, outlining legal and economic reasons why, in her view, the valuation should in all cases be calculated based on the expropriation date.

Damages award and costs

Based on a series of parameters and on the cash flows that the ulexite reserves would have generated if the concessions had not been expropriated, the tribunal awarded damages amounting to US$48,619,578. It also awarded interest, compounded annually, at the rate of one-year LIBOR plus two per cent. Bolivia was ordered to cover half of the claimants’ arbitration costs, and each party was ordered to cover its own legal fees and expenses.

Notes

The ICSID tribunal was composed of Gabrielle Kaufmann-Kohler (President appointed by the Chairman of the Administrative Council, Swiss national), Marc Lalonde (claimant’s appointee, Canadian national), and Brigitte Stern (respondent’s appointee, French national). The award is available at http://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/case-documents/italaw4389.pdf. Brigitte Stern’s partial dissent is available at http://www.italaw.com/sites/default/files/case-documents/italaw4388.pdf.

Authors

Inaê Siqueira de Oliveira is a Law student at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil.

Stefanie Schacherer is a Ph.D. candidate and a Teaching and Research Assistant at the Faculty of Law of the University of Geneva.

Matthew Levine is a Canadian lawyer and a contributor to IISD’s Investment for Sustainable Development Program.

Martin Dietrich Brauch is an International Law Advisor and Associate of IISD’s Investment for Sustainable Development Program, based in Latin America.